“…an organization of us, by us and for us.”

This is a special post written by Triangle CEO Coleman Nee, who is a Volunteer National Line Officer with Disabled American Veterans (DAV) and a Marine Corps Veteran of the Gulf War.

On November 11, 1918 at 11:00 am, the sound of gunfire, cannons and bombs went silent in Europe. It was the end of World War I. An Armistice had been declared and it was time to reconcile the immoral and obscene consequences of this senseless conflict. Over 17 million military and civilians had been killed in a span of 4 years, 3 months and 2 weeks. As horrific as this grim statistic is, it still does not account for the entire tragedy of the war. According to official sources, of the 60 million European military personnel who were mobilized, 7 million were permanently disabled, and 15 million were seriously injured. Among the soldiers mutilated and surviving in the trenches, approximately 15,000 sustained horrific facial injuries, causing them to undergo social stigma and marginalization when they returned home.

America entered the war relatively late in April of 1917, but in the span of 19 months it suffered over 116,000 military deaths and 200,000 wounded. To honor their service and sacrifices, the United States Congress adopted a resolution on June 4, 1926, requesting that President Calvin Coolidge “issue annual proclamations calling for the observance of November 11 with appropriate ceremonies and a Congressional Act approved May 13, 1938, made November 11 in each year a legal holiday: “a day to be dedicated to the cause of world peace and to be thereafter celebrated and known as ‘Armistice Day'”. Later, in wanting to recognize those that served during World War II, President Dwight D. Eisenhower signed a bill proclaiming November 11th as Veterans Day and called upon Americans everywhere to re-dedicate themselves to the cause of peace.

However, the fight for veterans who had incurred disabilities as a result of their service and needed services, training and inclusion in their communities was far from over. And (as is the case throughout the history of the struggle for disability justice) champions and passionate advocates were needed to lead the struggle.

In 1919, Marine veteran Albert Rindsberg was staying at the Harrison Club hotel in Cincinnati when he wandered into a heated conversation. A group of veterans were talking about how little was being done for disabled veterans in America. Rindsberg had been discharged the previous year and incurred disabilities in service. Thus, the conversation caught his interest.

The Great War had ended, and although a sense of victory and patriotism should have swept the nation, those feelings were overshadowed by a global influenza pandemic and a brutal postwar economy. Over 200,000 American injured servicemen returned home to a country that was not prepared to help them, resulting in thousands of veterans without jobs or proper medical care.

As Rindsberg listened, he was enthralled by the charismatic and thought-provoking points made by a fellow disabled veteran. That young man, Robert S. Marx, was the newly elected judge for the Cincinnati Superior Court and that meeting would plant the seed for what would become Disabled American Veterans.

“We had a common experience which bound us together,” Marx said about his idea to form a group to protect the interests of disabled veterans. “And we ought to continue through an organization of our own—an organization of us, by us and for us.”

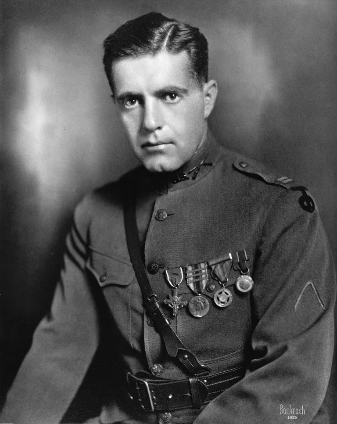

Marx had spent the better part of two years in combat tending to the needs of his men, often in dismal conditions and through unrelenting hardship. His own experiences and injuries during the war helped him develop a deep commitment to the care of his fellow soldiers and ultimately his fellow veterans.

In 1918, on a long and winding road from the regimental headquarters to Baâlon, France, Marx and his battalion came across several German prisoners being escorted behind the lines. The hill overlooked the town, which could not be entered and occupied until Marx and his men had driven the Germans off the ridge. From atop the hill, German forces rained fire down upon Marx and his battalion as they tucked away in the brush and tall grass. “The barrage was intense, and the shells began to drop with alarming accuracy near our battalion group,” Marx recorded in his account. “It seemed to us as if the range was lengthening, so we continued to advance. Then a shell struck almost in our midst. I did not hear it coming, and I seemed to be hit before I knew it or heard the noise. I only knew that I was hit in the head.”

That day was Nov. 10, and doctors would begin surgery on Marx around midnight. “I hovered between life and death in this hospital,” Marx recounted, unaware that the following morning, the Allies and German forces would sign the armistice, ending the war.

The so-called “war to end all wars,” even in its last hours, had proved deadly for many—2,738 men perished in that final day, right up until the bugle call sounded the start of the armistice. Historians estimate another 8,100 more were wounded or went missing, adding to the millions of casualties suffered during the course of the four-year conflict.

By all accounts, Marx was a hero; he received the Distinguished Service Cross, the nation’s second highest honor for valor, for his actions. But he still came home and faced the same reality as every other disabled veteran and non-veterans: the nation was not prepared to provide them the care and support they needed in the aftermath of the war.

When Marx returned home to Cincinnati, he was quickly elected the youngest judge to the Cincinnati Superior Court. He would also go on to have a storied law career as a skilled trial attorney as well as teach at his alma mater, the University of Cincinnati Law School. (Its library would eventually bear his name.) He even created a course, simply called “Facts,” that went on to be taught at law universities around the country.

With everything Marx had done for his country, his community and his professional field, it never would come close to the lasting effect he would have on millions of Americans with Disabilities for the next 100 years.

On that Christmas Day in 1919, when Marx gathered a group of disabled veterans together for dinner and camaraderie, he may not have realized the full magnitude of what he was setting in motion. But it was to be a pivotal moment for generations to come. He spent the remainder of his life in the pursuit of disability justice—both for veterans and his fellow Americans. A friend and adviser to Franklin D. Roosevelt, he gave voice to those who could not speak up for themselves.

Today, with more than 1 million members currently filling the ranks of the organization Marx created a century ago, DAV continues to help the men and women who have served our country, as well as their families, under a mission that includes the principle that this nation’s first duty to veterans is the rehabilitation and welfare of its wartime disabled. This principle envisions vocational rehabilitation and/or education to assist these veterans to prepare for and obtain gainful employment, enhanced opportunities for employment, job placement and self-employment, so that the full array of talents and abilities of veterans with disabilities are used productively and to their greatest levels.

As we celebrate this Veterans Day, it is with the spirit and vigor of Disability Rights champions like Robert Marx, that we should recommit ourselves to the principles of justice, civil rights and inclusion, for which that so many have served to secure and defend since the birth of our Republic.

Portions of the article were sourced from Disabled American Veterans (DAV). You can learn more about DAV at dav.org.